Banner Section

The Advancement of Healthcare Analytics

Points of View - Inner

Community Health Plans can Support the Triple Aim through High Integrity Data

At a recent healthcare information technology conference[1], industry experts had varying opinions and sometimes opposing views on healthcare organizations’ capabilities to improve health outcomes and the consumer experience, while improving affordability. These experts did agree on one thing: the healthcare industry is well behind many other consumer-based industries in leveraging data analytics to drive strategic and operational decisions.[2] The enormous pressure to close the data analytics gap, precipitated by consumers, experts and policymakers, leaves some healthcare organizations wondering where to begin. Value-based reimbursement, a cornerstone of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), demands that health plans evolve analytical maturity and capabilities.[3]

Kenny & Company’s big data “Lagging to Leading” maturity model[4] provides a framework that organizations can use to understand and then evolve their data analytics maturity level. As indicated in the maturity model, a key component to mature analytics is high integrity data. California’s county-based (or “community”) health plans lag behind their commercial counterparts[5] in collecting accurate, timely and complete data, referred to as data integrity domains. However, we contend that community health plans are uniquely positioned to influence the safety-net delivery system to improve data integrity. In this paper, we offer prescriptive techniques for community health plans to improve data integrity with their network providers, members and other stakeholders. In addition, we introduce Data Integrity Dashboards to monitor and sustain the necessary data integrity to support mature analytics.

The Triple Aim and the Future of Healthcare

Healthcare reform has changed how care is delivered, measured, managed and financed. The Triple Aim, reinvigorated as the design principle upon which the ACA[6] was built, delivers a compelling framework to support change. The Triple Aim framework, developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) “refers to the simultaneous pursuit of improving the patient experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.”[7] The figure below demonstrates the interdependencies between the three aims; one or more aims should not benefit at the expense of another.

Figure 1: IHI’s Triple Aim Triangle[8]

Healthcare leaders and academic experts are challenging the ideas of how healthcare is reimbursed by redefining outcomes to mean value, not merely output.[9] These same leaders go further by encouraging community health plans and their delivery systems to work in alignment and with a shared goal.[10] Calculating “value” requires mature analytical tools and knowledge, all of which requires high integrity data.

These nascent ideas also call on health plans to depart from the days when priorities focused on managing money, not care. Future healthcare policies will be guided, or even driven, by Triple Aim-inspired principles[11], fueling the growing need for strong analytics. Today, 16 quality measures have been tied to value-based reimbursement for Medicare providers that if not met, could result in financial penalties.[12] While contentious, Medicare payment reform is an indicator for future reimbursement changes, if not already present today through Medi-Cal’s Health Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and other payment and member auto assignment-based measures. High integrity data is essential to support the detailed calculations, reporting and analytics required by value-based reimbursement.

New research suggests that providers should be added as the fourth aim[13], further suggesting that providers are essential in the development and implementation of key change initiatives in healthcare. Therefore, health plans must work collaboratively with providers to address the integrity domains of data accuracy, timeliness and completeness.

Community Health Plans are Well Position to Lead Data Integrity

The California Health Care Foundation defines community health plans as “county-based health plans that are public entities and organized through one or more counties to ensure comprehensive care for Medi-Cal and, in some cases, other publicly insured populations, such as county employees”[14]. Inherent to community health plans is the mission to preserve and improve the delivery system that serves predominately low-income individuals and families.[15]

For example, of the more than 2.2 million Medi-Cal managed care beneficiaries in Los Angeles County, 65 percent are members of the county’s community health plan, L.A. Care Health Plan.[16] This trend is not limited to Los Angeles. When combining the counties that have community health plans, 75 percent of all Medi-Cal managed care beneficiaries are members of community health plans.[17]

The community health plan model typically concentrates members into a single or limited number of delivery systems. From the perspective of delivery systems that traditionally serve the Medi-Cal population, community health plans are ubiquitous, as well as a significant stakeholder in their success as a delivery system. The relationship between community health plans and their delivery systems results in a large group of providers working more in alignment with community health plans than they typically would with commercial health plans. Community health plans, then, are positioned to achieve meaningful and significant impact to their safety-net delivery networks, including data integrity improvement.

We introduce a data-focused dashboard for health plans to monitor data integrity across delivery systems and within integrity domains as well as target high impact improvement areas. Also, we present techniques that community health plans can employ to positively impact data integrity.

The Journey to Value-Based Reimbursement Begins with High Data Integrity

Data Integrity Dashboard

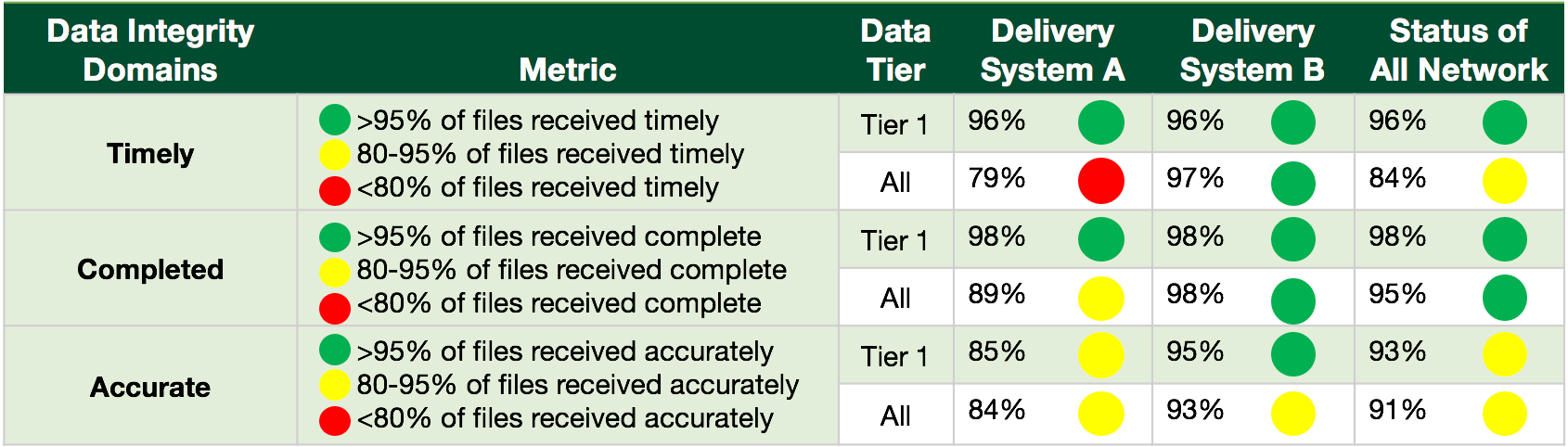

The Data Integrity Dashboard (DID) is critical for generating a data integrity baseline, then tracking improvements generated by applying the techniques we will be presenting. Performance standards are established using pre-defined integrity domains, including timeliness, completeness and accuracy. Figure 2 demonstrates how a community health plan can monitor and be prompted to mitigate potential obstacles on the road towards data integrity. For the purposes of this paper, the dashboard divides data sources into two tiers:

- Tier 1 – data that specifically support measures that draw conclusions on member care, experience, and costs.

- Tier 2 – all other data.

The DID format easily accommodates additional Tiers as defined by a health plan’s strategy. The categorization of data enables executives to make informed decisions about where to direct resources and inform the community health plan’s project prioritization process. The DID is not limited to internal use; it also adds value to demonstrate the effectiveness of data improvement efforts by providers and other entities that are sources of data.

Figure 2: Sample Data Integrity Dashboard (DID) by Delivery System.

Many conclusions can be drawn from the sample dashboard shown in Figure 2. For example, Delivery System A is performing poorly on the timely domain as an average across their data and yet performing up to standards for Tier 1 data. The DID also indicates that Delivery System A’s data accuracy is at risk for poor performance. In this scenario, a community health plan executive facing scarce resources may choose to prioritize a project or program to improve accuracy over timeliness, assuming their strategy is to use Tier 1 data to create value-based measures on member care, experience, and cost.

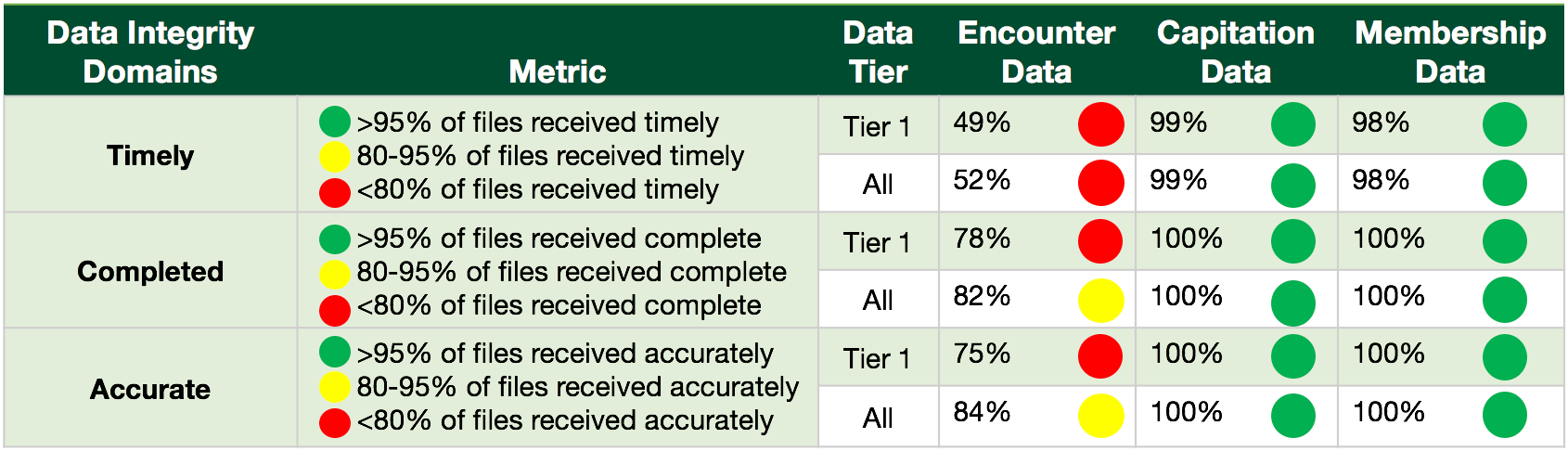

Figure 3: Sample Data Integrity Dashboard (DID) by Data Type.

To demonstrate its flexibility, the DID in Figure 3 monitors integrity by data type, instead of by delivery system. The chart in Figure 3 suggests that there are no problems with data integrity in the capitation and membership data as defined by the metrics. However, encounter data has issues in all domains. Using the dashboard with these metrics could result in projects or programs to resolve data integrity issues specific to types of data, which may vary by source. The dashboard can also be multi-dimensional by first dividing up metrics by delivery system, then by data type for each delivery system. Adding more dimensions enables health plans to gain a more complete picture of the accuracy, timeliness, and completeness in areas beyond sources and type of data, and therefore better equipped to make informed strategic decisions.

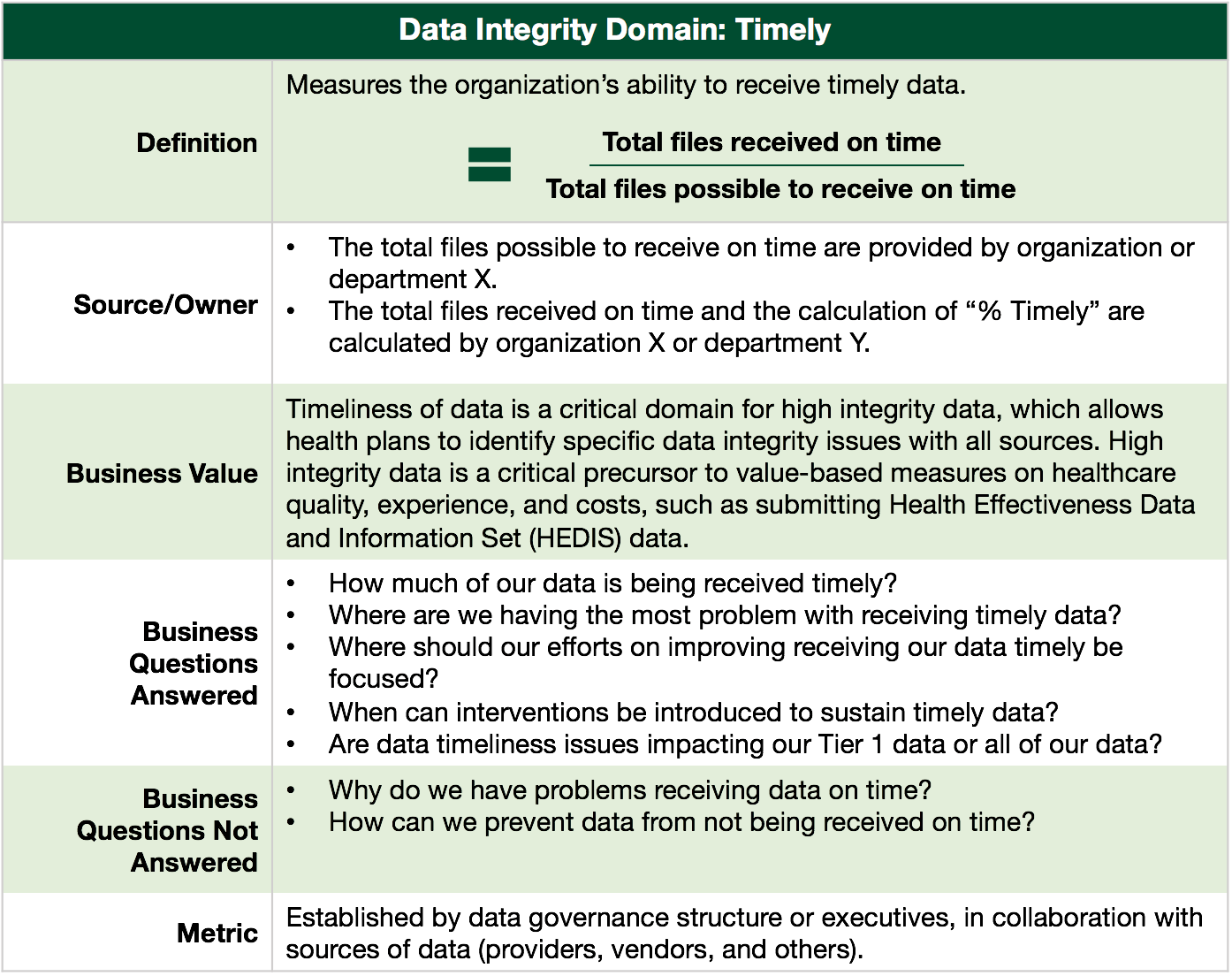

Prior to implementing a DID, it is important to invest time to establish and communicate each data integrity domain definition. The metadata for each domain includes the definition, sources and owners, business value to the organization, business questions answered and not answered, and the benchmark decision-making process. Each element of the domain’s metadata is listed below.

- Definition: The definition includes the calculation of the domain’s metric and a short description.>

- Source/Owner: The sources and owners of the data used in the calculation are outlined in this section, specified by organization, department, role and name.

- Business Value: This section clearly explains the value of tracking this domain to the overall strategy of the health plan.

- Business Questions Answered: A list of questions in which this domain answers ties actionable steps to the domain’s metrics.

- Business Questions Not Answered: It is important to list related questions that are not answered by the metric, to manage the expectations of the DID’s recipients.

- Metric: This section identifies how the metrics (or performance benchmarks) were established and a brief description of the process for changing the benchmark.

Figure 4 is an example of the metadata for the Timeliness domain.

Figure 4: Sample Measure Description

Directed by the results of the dashboard, health plans can take actionable steps, typically through a project or program, to resolve data integrity issues. The DID analysis may result in a myriad of potential projects and programs, so it is critical that prioritization criteria include how the data is tied to overall care, experience, and cost, and integrated into a portfolio for prioritization and execution (refer to Kenny & Company’s whitepaper on portfolio management[18]). Efforts targeting data that are essential to the Triple Aim have a distinct advantage over those that do not.

Techniques for Improving Data Integrity

Once the DID is used to establish a definition and performance standards for high integrity data, health plans are able to identify specific data integrity issues across sources (e.g. delivery systems, internal sources, state agencies). Below, we introduce techniques for health plans to improve data integrity in partnership with the delivery system and other data sources.

- Implement Provider Incentive Programs: Health plans can create an incentive program to hold providers accountable to support data integrity efforts. For example, the incentive program can provide an additional dollar amount to capitation payments if providers achieve period goals in the various data integrity domains. Health plans benefit from ensuring high integrity data and providers benefit from receiving payment, in addition to establishing a culture of data accountability.

- Offer Provider Technical Support: Delivery systems that traditionally provide services to Medi-Cal beneficiaries and the uninsured may lack the technical expertise and resources to adopt new and innovative ways to improve data integrity. Health Plans can provide technical support to IT departments at these delivery systems.

- Manage Vendor Data: Health plans may rely on vendors, such as an external enrollment system or patient portal, to collect data that is timely, complete, and accurate. Health plans can include standards and rules of engagement for the data it receives from its vendor contracts and agreements. A lack of contracted standards increases the risk that quality of the data used for analytics is compromised. Furthermore, no rules of engagement could lead to increased vendor costs to resolve data integrity issues post implementation.

- Introduce Peer to Peer Medical/Physician Group Best Practices: Health plans can showcase best practices to improve and sustain data integrity within the provider community. Health plans can schedule a “roadshow” to visit provider practices to demonstrate best practices on a variety of data integrity domains, such as collecting data through electronic medical records, realignment of data entry tasks from clinicians to non-clinicians and improving electronic file sharing to the health plan.

- Offer Targeted Provider Workforce Training & Education: If the root cause of data integrity is at the workforce level, a training and education program can be uniformly designed to address the issues. For example, training providers to accurately complete the Medi-Cal Child Health and Disability Prevention (PM160) form can significantly improve health plan data integrity in this area.

- Encourage Completion of State-Driven Member Survey: Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys ask health plan members to report on and evaluate their experiences with healthcare. Community health plans are required by the Department of Health Care Services to use CAHPS to measure quality. Health plans can use incentives, community outreach, and outbound calls to target members to increase survey responses. Survey results are a critical input to data analysis and interventions around member retention.

- Implement Customized Member Survey to Measure Experience: Health plans can develop an annual survey, targeting a segment of their membership with the objective of collecting additional data to assess patient experience. The survey would be a source of information on the six aims of healthcare experience as defined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM); Safe, Effective, Timely, Patient-Centered, Equitable, and Efficient.

- Leverage Member Touch Points: Health plans can identify all member touch points and assess the feasibility to leverage these touch points to update and confirm demographic information. For example, call centers can modify their outreach workflow to view the system of record and validate or update a member’s information when they call. Patient portals can prompt to confirm or change demographics at log in.

- Improve Source Data from Grievances and Complaints: Harnessing member grievances and complaints as a critical data source to measure the member experience is a valuable health plan input to applying targeted and actionable categories on each grievance. For example, categories that can improve meaningful analysis include; member grievance volume, type (e.g., clinical, operational, administrative), location (e.g., clinic, hospital, phone) and demographic categories.

- Evaluate State-Driven Data: Unlike commercial plans where member demographic data is provided by employers or individual consumers, community health plans rely on this data from the State, through the Medi-Cal program. Given the significant impact of demographic information on quality analytics and that community health plans have a large segment of their membership coming from Medi-Cal, health plans can establish roles and responsibilities within their organization to be gatekeepers and drivers for reconciliation of data from the State.

Conclusion

The implementation of healthcare reform is changing how healthcare is being delivered, measured, managed and financed. Mature analytical capabilities supported by high data integrity is necessary to prepare for many of the changes such as Medicare’s upcoming value-based reimbursement rules.

The unique role of community health plans and their strong relationship to safety-net delivery systems positions them to monitor and improve data integrity. Community health plans can work collaboratively with providers to improve data accuracy, timeliness, and completeness. Data integrity domains areas can be monitored using the Data Integrity Dashboard, tailored to fit a health plan’s current strategies.

In the era of big data, community health plans can support the Triple Aim through prioritizing and monitoring valuable data through data integrity efforts, making a substantial impact to their delivery systems, in addition to sustaining their relevance in the changing healthcare landscape.

About the Authors

Shani S. Trudgian is a Partner at Kenny & Company with 21 years in management consulting and business development experience, focused exclusively in health care. She has guided her clients through health reform readiness strategy, health reform implementation, process re-engineering, acquisitions, ICD-10 readiness approach, Accountable Care Organization implementation, Electronic Health Records roll-out, ambulatory heath care delivery refinement, business model analysis, organizational development, change leadership and in other strategic areas. Shani’s industry experience includes medical groups/IPA, county/ private/ teaching hospitals, health plans (public/private), health systems, safety net clinics, dental insurance, oral health delivery, non-profit grant-making philanthropy, and behavioral health organizations. Shani holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Business with an emphasis in Information Systems from the University of Washington.

Adrian Núñez is a Manager at Kenny & Company. He has over 13 years of leadership, operations, and management experience in publicly sponsored health coverage programs, managed care, and stakeholder management. He has participated in and guided organizations with program management, healthcare reform readiness, health coverage regulatory compliance, enrollment & eligibility operations, QNXT enrollment & eligibility configuration, One-e-App configuration and user training. He also has significant experience working with and development of community based networks, initiatives, advisory groups, and coalitions to achieve strategic goals. Adrian holds a Bachelor of Science in Biochemistry from University of California at Davis and is a graduate of the Coro Fellows Program in Public Affairs.

About Kenny & Company

Kenny & Company is a management consulting firm offering Strategy, Operations and Technology services to our clients.

We exist because we love to do the work. After management consulting for 20+ years at some of the largest consulting companies globally, our partners realized that when it comes to consulting, bigger doesn’t always mean better. Instead, we’ve created a place where our ideas and opinions are grounded in experience, analysis and facts, leading to real problem solving and real solutions – a truly collaborative experience with our clients making their business our business.

We focus on getting the work done and prefer to let our work speak for itself. When we do speak, we don’t talk about ourselves, but rather about what we do for our clients. We’re proud of the strong character our entire team brings, the high intensity in which we thrive, and above all, doing great work.

Notes

- IHT2 Health IT Summit 2015, Institute for Health Technology Transformation, www.ihealthtran.com

- At iHT2-San Francisco, Healthcare IT Leaders See a (Very) Long Data Analytics Journey Ahead, March 3, 2015. Healthcare Informatics Magazine, www.healthcareinformatics.com

- How Analytics Will Help You Achieve the Triple Aim, HealthCatalyst, www.healthcatalyst.com

- Holly Macke, Will Yen, Measuring your Big Data Maturity, Kenny & Company Point of View, Dec 2014. www.michaelskenny.com

- Quality of care in Medicaid managed care and commercial health plans. Landon BE1, Schneider EC, Normand SL, Scholle SH, Pawlson LG, Epstein AM. JAMA. 2007 Oct 10;298 (14):1674-81.

- McDonough JE. Health system reform in the United States. Int J Health Policy Manag 2014; 2: 5–8. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2014.02

- Ninon Lewis, A Primer on Defining the Triple Aim, www.ihi.org

- Stiefel M, Nolan K. A Guide to Measuring the Triple Aim: Population Health, Experience of Care, and Per Capita Cost. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2012. (Available on www.IHI.org)

- Donald M. Berwick, Thomas W. Nolan and John Whittington, The Triple Aim: Care, Health, and Cost, Health Affairs, 27, no.3 (2008): 759-769

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Sabriya Rice, Reform Update: Some questions the value of value-based purchasing. August 2014. Modern Healthcare Article, www.modernheatlhcare.com

- Thomas Bodenheimer, MD, Christine Sinsky, MD, From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider, Annals of Family Medicine, Vol. 12, No. 6, Nov/Dec 2014

- Ibid

- County-based Health Plans & Insurers, California Health Care Foundation Almanac Quick Reference Guide. www.chcf.org

- Medi-Cal Enrollment Report Fiscal Year Comparison, October 2014, Local Health Plans of California, www.lhpc.org

- Ibid

- Brent Weigel, Setting the Foundation for Strategic Portfolio Planning, Kenny & Company Point of View, Dec 2013, www.michaelskenny.com

This article was first published on www.michaelskenny.com on March 3, 2015. The views and opinions expressed in this article are provided by Kenny & Company to provide general business information on a particular topic and do not constitute professional advice with respect to your business.